No Money, No Court Appeal While SMU President Lily Kong Gets Away Scot-free With Lying About NUS COI

27 May 2019

Dear friends,

It’s been some time since my last blog, and I have a lot to catch up on in this blog.

Thank you all for your concern and requests for updates. Your continued support means a lot to me. In recent months, I have suffered a great deal of stress and aggravation, as NUS has exerted a great deal of pressure on me to stop me from appealing the NUS case to the Court of Appeal. In addition, a law firm that I had previously engaged from late 2012 to early 2014, when I still had money to pay lawyers, tried to take advantage of the loss of my High Court case and my inability to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

My current attempts to appeal to the Singapore Court of Appeal

As I mentioned in my previous blog, I am now (in 2019) continuing to try to appeal to the Court of Appeal, which I have a legal right to do, but NUS is now doing everything it can to block me from appealing to the Court of Appeal. Is NUS afraid to face me before the Court of Appeal?

I blogged about the steps that I have taken to initiate an appeal of Suit 667/2012 to the Court of Appeal dated 31 December 2018

To summarise, I filed the necessary papers (the “Notice of Appeal”) on 8 August 2018 for the appeal, but my Notice of Appeal was rejected because I could not afford to furnish the $20,000 Security for Costs (security deposit) for the benefit of NUS.

I was frantic and lost. Since I did not have a lawyer anymore, I sought pro-bono advice in the Community Justice Centre located in the Singapore State Courts.

On the advice of the pro bono lawyer, I filed an Application to the Court of Appeal for a dispensation or waiver of the Security for Costs and an extension of time to refile the Notice of Appeal out of time, in an Originating Summons that I filed with the Court of Appeal (“OS to CA”) on 31 December 2018.

My application to the Court of Appeal in the Originating Summons that I filed on 31 December 2018 contained two prayers:

(a) an application for an extension of time to file the Notice of Appeal out of time, and

(b) an application for a waiver of the Security for Costs (in plain English, the security deposit for the appeal).

A catch 22 situation (1-15 January 2019)

After filing the Originating Summons with the Court of Appeal on 31 December 2018, I received a notification that the Court had rejected my application.

I wrote to the Supreme Court Registry to ask about the reason for the rejection.

On 15 January 2019, the Court responded that the Court rejected my “OS to CA” (Originating Summons to the Court of Appeal) because I did not furnish a Security for Costs (security deposit) for the “OS to CA.” In other words, the Court told me that it will not hear me at all, unless I can afford to deposit thousands of dollars as a “security deposit.”

I was stunned!!! As a citizen of Singapore, I supposedly have a legal right to appeal. What good is it that Singaporean citizens supposedly have a legal right to appeal, if the Court can deny me my right to appeal just because I cannot afford to pay thousands of dollars for a security deposit? I am now trapped in a vicious cycle – in order to get the Court of Appeal to be willing to hear my application to waive the $20,000 Security for Costs, I have to pay yet another set of Security for Costs...

There are now two sets of security deposits which I have to pay in order for me to be heard by the Court of Appeal:

(i) the Security for Costs accompanying the Notice of Appeal dated 8 August 2018 (SG $20,000)

(ii) the Security for Costs accompanying the Originating Summons to the Court of Appeal dated 31 December 2018 (SG$?)

I still do not have any idea how much is needed for the 2nd set of security deposit, but I believe the two sets will add up to a maximum of SG$40,000.

It looks like there is no way for me to ever get out of this vicious cycle. Except with money. Only money can clear the way to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

Is it fair that the wrongdoer (NUS) gets to be the gatekeeper to decide whether or not I can have access to justice (15 January to 1 March 2019)?

Incredibly, the Court has actually given NUS the power to decide whether or not I will be allowed to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

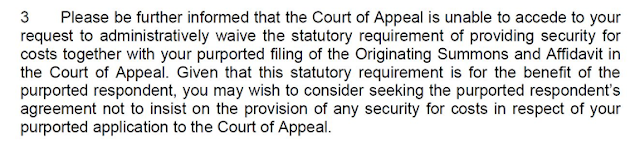

In the Court’s reply to me on 15 January 2019, the Court Registry also stated that I consider asking NUS “not to insist on the provision of any security for costs in respect of [my] purported application to the Court of Appeal.”

It is manifestly unfair that NUS, the wrongdoer, has the power to determine whether or not my appeal will be heard by the Court of Appeal, due to the fact that I am “impecunious,” in the sense that I cannot afford to make the payments for the Security for Costs.

The reason that I am now “impecunious” is due to wrongdoing by NUS, which had sabotaged my career, and the funds that I had managed to save have been spent on my efforts to obtain justice through legal proceedings these seven (7) years.

Thus, the Court system is now allowing NUS to benefit from its own wrongdoing. NUS caused me to become “impecunious” after NUS destroyed my career, and now (in 2019) the Court system has allowed NUS to take advantage of my impecuniosity and block me from appealing to the Court of Appeal.

It is very telling that the High Court (per Justice Woo Bih Li) has now officially found that NUS and Vice-Provost Lily Kong were “wrong” in my case – since Lily Kong was acting in the name of NUS in my case, the Court’s findings that Lily Kong was “wrong” means that the Court also found that NUS was “wrong” too. So, this wrongdoing by NUS and Lily Kong is now no longer “alleged” or a mere “allegation.” Instead, it is an established fact, confirmed by the High Court. Regarding the Court's findings that NUS was “wrong” see Judgment for High Court Suit 667/2012 at paragraphs [229]-[231], [234] and [241].

I am also puzzled because the pro-bono lawyer in the Community Justice Centre had advised me that there was indeed a legal precedent for the Court to waive the Security for Costs. That was why he told me to file the OS to CA. That was why he told me to file the Originating Summons with the Court of Appeal, which I did on 31 December 2018.

When I read the Court Registry’s letter dated 15 January 2019, I realised that it was totally unfair, and I did not think it is right that NUS gets to be the gatekeeper for my access to the Court of Appeal, or that the Court system would give NUS that power, but out of respect for the Court, I wrote to NUS to make the request to not insist on the Security for Costs.

NUS said “no.” I was not surprised at all.

It has finally come to this stage – due to my inability to furnish SG$20,000 to SG$40,000 to make two security deposits for the benefit of NUS, I would not be able to appeal my case no matter how legitimate my claims might be.

The cost hearing (13 May 2019)

On 11 January 2019, an NUS lawyer wrote to me to seek clarification regarding the contents of my blog dated 31 December 2018, specifically, my intention to appeal the High Court judgment. I informed the NUS lawyer that indeed, I wanted to appeal. The very next day (16 January 2019), after receiving my reply, the NUS lawyer wrote to Court to ask for a date to be fixed for the Cost Hearing for Suit 667 of 2012 on the grounds that there was no appeal forthcoming and so the Court should go ahead with a hearing to decide the cost to award NUS. A first cost hearing was eventually fixed and heard in May, but it could not be completed because NUS failed to prepare the cost breakdown. I will update in my next post about the hearing on costs.

I will update in my next post about the hearing on costs. The main issue regarding costs is that NUS has been pushing the Court to have the costs hearing. Although NUS had asked for almost $700,000 in costs leading up to the hearing on 13 May 2019 – NUS reduced the sum and asked for $400,000 legal fees during the hearing. This amount would certainly bankrupt me. However, it must be kept in mind that NUS might still appeal against the High Court's costs order, and NUS could ask the Court of Appeal to order me to pay a larger amount.

Where is justice for impecunious people?

I return to the issue of justice for impecunious people.

As I have mentioned, I was stunned by the Supreme Court’s suggestion that I write to NUS to ask NUS not to insist on the security deposit. It’s unfair that, even though I have a strong case for appeal to the Court of Appeal, the defendant NUS, which has been found by the High Court to have been guilty of wrongdoing, gets to decide whether or not the Court of Appeal will hear my application, simply because I cannot afford to pay for the Security for Costs for my applications to the Court for the benefit of NUS.

Regarding the Court's findings that NUS was “wrong” see Judgment for High Court Suit 667/2012 at paragraphs [229]-[231], [234] and [241].

The idea of allowing NUS to decide whether or not I can appeal to the Court of Appeal, which is precisely what the Court has done, resembles the plot of an absurd fictional story, such as Franz Kafka's books Der Prozess (translated as The Trial) and Das Schloss (translated as The Castle). It is shocking that something like this could happen in Singapore today.

The Court Registry's rejection of my applications because I could not afford to pay the “Security for Costs,” and the Court Registry's suggestion that I write to NUS, are inconsistent with “the over-arching principle that an impecunious claimant must not be denied access to the courts, even if this would result in injustice to a successful defendant who may be unable to recover his legal costs.” This is a legal principle that has been endorsed by the Singapore Court of Appeal in Ho Wing On Christopher and Others v ECRC Land Pte Ltd (in liquidation) [2006] SGCA 25 at [70]. In the same judgment, the Court of Appeal observed (at [71]) that: “it is trite law that poverty is no bar to a litigant who is a natural person.” What good are these high-sounding “principles,” if the Court rejects an application because the impecunious applicant cannot afford to pay the “Security for Costs?”

What is the point of the Court promising that “an impecunious claimant must not be denied access to the courts” if that access is made dependent upon the applicant first obtaining the permission of the opposing party, who has already been found to be a wrongdoer?

Although I have an automatic legal right of appeal against the High Court’s decision, my lack of funds has become an impediment in my pathway to justice. This is especially appalling since my case is a matter of public interest, involving institutional wrongdoing by a public body including dishonesty, corruption, abuse of power, cover-up, and retaliation against a whistle-blower by NUS.

The extra efforts that I have to put in, the second application that I had to file with the Court in order to appeal to the Court of Appeal (the OS to CA), and the difficulties I've encountered along the way, underscore how tedious and difficult it is for ordinary Singaporeans who do not have the financial resources to seek justice in court.

The Honourable Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon has observed that, in “the pathway to justice for most litigants” the “first and probably the most critical hurdle is the high cost of litigation.” Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon has also observed that “the cost of legal services in Singapore must now be acknowledged as being on the high side” and noted that: “It is cold comfort to those who seek justice to say that we have a great legal system, if it is priced out of their reach.”

(Source: Opening Address of the Honourable the Chief Justice at the Litigation Conference 2013 Organised by the Civil Practice Committee of the Law Society of Singapore 31 January 2013)

This whole episode has caused me to suffer a sense of despair – what is a “legal right” which is in actual practice, an entitlement that is contingent upon having the wealth to gain access to that “legal right?”

The Court has denied me my legal right to appeal

Supposedly, every Singaporean has a legal right to appeal, but my case shows that the Singapore court system has allowed this right to appeal to operate only in tandem with privileged circumstances and stifle the right of appeal of Singaporeans like me who are suffering from financial distress and impecuniosity.

The legal right of all Singaporeans to appeal has been repeatedly endorsed by the Singapore Court of Appeal in several written judgments. For example, in Virtual Map (Singapore) Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority [2009] 2 SLR(R) 558 at paragraph [30], the Singapore Court of Appeal noted “the principle that there should be one tier of appeal as of right in civil actions in Singapore. Unsuccessful litigants in such cases should be entitled to appeal as of right to the Court of Appeal.” The Singapore Court of Appeal noted that there is “one tier of appeal as a matter of right” in its written judgment in IW v IX [2005] SGCA 48 at paragraph [22]. More recently, the Singapore Court of Appeal noted that “any judgment or order of the High Court is ordinarily appealable as of right” (Sinwa SS (HK) Co Ltd v Nordic International Ltd [2014] SGCA 63 at paragraph [32].

How do the statements quoted above square with my helplessness in attempting to gain access to the Court of Appeal?

Every Singaporean should be frightened and outraged by my case, because, if a major public body like NUS can get away scot-free with blatant abuse of power, corruption, cover-up and retaliation against a whistle-blower, while spending at least $700,000 dollars (as NUS has claimed) fighting a legal battle against me in the High Court, then ANY public body in Singapore can get away with doing these things to ANY Singaporean (or, at least, to any ordinary Singaporean who is not a member of the privileged and entitled “elite” class).

My case shows that a public body in Singapore like NUS is “above the law” and can get away with abuse of power scot-free, with zero accountability and total impunity. My case will embolden other public bodies and elites to engage in abuse of power, cover-up and retaliation just like NUS did to me.

Please see the video of the 17-minute speech about my case that I gave at Hong Lim Park, Singapore, on 16 March 2019.

For more information about my case, see the following articles:

PayLah!

Dear friends,

It’s been some time since my last blog, and I have a lot to catch up on in this blog.

Thank you all for your concern and requests for updates. Your continued support means a lot to me. In recent months, I have suffered a great deal of stress and aggravation, as NUS has exerted a great deal of pressure on me to stop me from appealing the NUS case to the Court of Appeal. In addition, a law firm that I had previously engaged from late 2012 to early 2014, when I still had money to pay lawyers, tried to take advantage of the loss of my High Court case and my inability to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

My current attempts to appeal to the Singapore Court of Appeal

As I mentioned in my previous blog, I am now (in 2019) continuing to try to appeal to the Court of Appeal, which I have a legal right to do, but NUS is now doing everything it can to block me from appealing to the Court of Appeal. Is NUS afraid to face me before the Court of Appeal?

I blogged about the steps that I have taken to initiate an appeal of Suit 667/2012 to the Court of Appeal dated 31 December 2018

To summarise, I filed the necessary papers (the “Notice of Appeal”) on 8 August 2018 for the appeal, but my Notice of Appeal was rejected because I could not afford to furnish the $20,000 Security for Costs (security deposit) for the benefit of NUS.

I was frantic and lost. Since I did not have a lawyer anymore, I sought pro-bono advice in the Community Justice Centre located in the Singapore State Courts.

On the advice of the pro bono lawyer, I filed an Application to the Court of Appeal for a dispensation or waiver of the Security for Costs and an extension of time to refile the Notice of Appeal out of time, in an Originating Summons that I filed with the Court of Appeal (“OS to CA”) on 31 December 2018.

My application to the Court of Appeal in the Originating Summons that I filed on 31 December 2018 contained two prayers:

(a) an application for an extension of time to file the Notice of Appeal out of time, and

(b) an application for a waiver of the Security for Costs (in plain English, the security deposit for the appeal).

A catch 22 situation (1-15 January 2019)

After filing the Originating Summons with the Court of Appeal on 31 December 2018, I received a notification that the Court had rejected my application.

I wrote to the Supreme Court Registry to ask about the reason for the rejection.

On 15 January 2019, the Court responded that the Court rejected my “OS to CA” (Originating Summons to the Court of Appeal) because I did not furnish a Security for Costs (security deposit) for the “OS to CA.” In other words, the Court told me that it will not hear me at all, unless I can afford to deposit thousands of dollars as a “security deposit.”

I was stunned!!! As a citizen of Singapore, I supposedly have a legal right to appeal. What good is it that Singaporean citizens supposedly have a legal right to appeal, if the Court can deny me my right to appeal just because I cannot afford to pay thousands of dollars for a security deposit? I am now trapped in a vicious cycle – in order to get the Court of Appeal to be willing to hear my application to waive the $20,000 Security for Costs, I have to pay yet another set of Security for Costs...

There are now two sets of security deposits which I have to pay in order for me to be heard by the Court of Appeal:

(i) the Security for Costs accompanying the Notice of Appeal dated 8 August 2018 (SG $20,000)

(ii) the Security for Costs accompanying the Originating Summons to the Court of Appeal dated 31 December 2018 (SG$?)

I still do not have any idea how much is needed for the 2nd set of security deposit, but I believe the two sets will add up to a maximum of SG$40,000.

It looks like there is no way for me to ever get out of this vicious cycle. Except with money. Only money can clear the way to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

Is it fair that the wrongdoer (NUS) gets to be the gatekeeper to decide whether or not I can have access to justice (15 January to 1 March 2019)?

Incredibly, the Court has actually given NUS the power to decide whether or not I will be allowed to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

In the Court’s reply to me on 15 January 2019, the Court Registry also stated that I consider asking NUS “not to insist on the provision of any security for costs in respect of [my] purported application to the Court of Appeal.”

<extract from the letter from the Court Registry on 15 January 2019>

It is manifestly unfair that NUS, the wrongdoer, has the power to determine whether or not my appeal will be heard by the Court of Appeal, due to the fact that I am “impecunious,” in the sense that I cannot afford to make the payments for the Security for Costs.

The reason that I am now “impecunious” is due to wrongdoing by NUS, which had sabotaged my career, and the funds that I had managed to save have been spent on my efforts to obtain justice through legal proceedings these seven (7) years.

Thus, the Court system is now allowing NUS to benefit from its own wrongdoing. NUS caused me to become “impecunious” after NUS destroyed my career, and now (in 2019) the Court system has allowed NUS to take advantage of my impecuniosity and block me from appealing to the Court of Appeal.

It is very telling that the High Court (per Justice Woo Bih Li) has now officially found that NUS and Vice-Provost Lily Kong were “wrong” in my case – since Lily Kong was acting in the name of NUS in my case, the Court’s findings that Lily Kong was “wrong” means that the Court also found that NUS was “wrong” too. So, this wrongdoing by NUS and Lily Kong is now no longer “alleged” or a mere “allegation.” Instead, it is an established fact, confirmed by the High Court. Regarding the Court's findings that NUS was “wrong” see Judgment for High Court Suit 667/2012 at paragraphs [229]-[231], [234] and [241].

When I read the Court Registry’s letter dated 15 January 2019, I realised that it was totally unfair, and I did not think it is right that NUS gets to be the gatekeeper for my access to the Court of Appeal, or that the Court system would give NUS that power, but out of respect for the Court, I wrote to NUS to make the request to not insist on the Security for Costs.

NUS said “no.” I was not surprised at all.

It has finally come to this stage – due to my inability to furnish SG$20,000 to SG$40,000 to make two security deposits for the benefit of NUS, I would not be able to appeal my case no matter how legitimate my claims might be.

The cost hearing (13 May 2019)

On 11 January 2019, an NUS lawyer wrote to me to seek clarification regarding the contents of my blog dated 31 December 2018, specifically, my intention to appeal the High Court judgment. I informed the NUS lawyer that indeed, I wanted to appeal. The very next day (16 January 2019), after receiving my reply, the NUS lawyer wrote to Court to ask for a date to be fixed for the Cost Hearing for Suit 667 of 2012 on the grounds that there was no appeal forthcoming and so the Court should go ahead with a hearing to decide the cost to award NUS. A first cost hearing was eventually fixed and heard in May, but it could not be completed because NUS failed to prepare the cost breakdown. I will update in my next post about the hearing on costs.

I will update in my next post about the hearing on costs. The main issue regarding costs is that NUS has been pushing the Court to have the costs hearing. Although NUS had asked for almost $700,000 in costs leading up to the hearing on 13 May 2019 – NUS reduced the sum and asked for $400,000 legal fees during the hearing. This amount would certainly bankrupt me. However, it must be kept in mind that NUS might still appeal against the High Court's costs order, and NUS could ask the Court of Appeal to order me to pay a larger amount.

Where is justice for impecunious people?

I return to the issue of justice for impecunious people.

As I have mentioned, I was stunned by the Supreme Court’s suggestion that I write to NUS to ask NUS not to insist on the security deposit. It’s unfair that, even though I have a strong case for appeal to the Court of Appeal, the defendant NUS, which has been found by the High Court to have been guilty of wrongdoing, gets to decide whether or not the Court of Appeal will hear my application, simply because I cannot afford to pay for the Security for Costs for my applications to the Court for the benefit of NUS.

Regarding the Court's findings that NUS was “wrong” see Judgment for High Court Suit 667/2012 at paragraphs [229]-[231], [234] and [241].

The idea of allowing NUS to decide whether or not I can appeal to the Court of Appeal, which is precisely what the Court has done, resembles the plot of an absurd fictional story, such as Franz Kafka's books Der Prozess (translated as The Trial) and Das Schloss (translated as The Castle). It is shocking that something like this could happen in Singapore today.

The Court Registry's rejection of my applications because I could not afford to pay the “Security for Costs,” and the Court Registry's suggestion that I write to NUS, are inconsistent with “the over-arching principle that an impecunious claimant must not be denied access to the courts, even if this would result in injustice to a successful defendant who may be unable to recover his legal costs.” This is a legal principle that has been endorsed by the Singapore Court of Appeal in Ho Wing On Christopher and Others v ECRC Land Pte Ltd (in liquidation) [2006] SGCA 25 at [70]. In the same judgment, the Court of Appeal observed (at [71]) that: “it is trite law that poverty is no bar to a litigant who is a natural person.” What good are these high-sounding “principles,” if the Court rejects an application because the impecunious applicant cannot afford to pay the “Security for Costs?”

What is the point of the Court promising that “an impecunious claimant must not be denied access to the courts” if that access is made dependent upon the applicant first obtaining the permission of the opposing party, who has already been found to be a wrongdoer?

Although I have an automatic legal right of appeal against the High Court’s decision, my lack of funds has become an impediment in my pathway to justice. This is especially appalling since my case is a matter of public interest, involving institutional wrongdoing by a public body including dishonesty, corruption, abuse of power, cover-up, and retaliation against a whistle-blower by NUS.

The extra efforts that I have to put in, the second application that I had to file with the Court in order to appeal to the Court of Appeal (the OS to CA), and the difficulties I've encountered along the way, underscore how tedious and difficult it is for ordinary Singaporeans who do not have the financial resources to seek justice in court.

The Honourable Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon has observed that, in “the pathway to justice for most litigants” the “first and probably the most critical hurdle is the high cost of litigation.” Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon has also observed that “the cost of legal services in Singapore must now be acknowledged as being on the high side” and noted that: “It is cold comfort to those who seek justice to say that we have a great legal system, if it is priced out of their reach.”

(Source: Opening Address of the Honourable the Chief Justice at the Litigation Conference 2013 Organised by the Civil Practice Committee of the Law Society of Singapore 31 January 2013)

This whole episode has caused me to suffer a sense of despair – what is a “legal right” which is in actual practice, an entitlement that is contingent upon having the wealth to gain access to that “legal right?”

The Court has denied me my legal right to appeal

Supposedly, every Singaporean has a legal right to appeal, but my case shows that the Singapore court system has allowed this right to appeal to operate only in tandem with privileged circumstances and stifle the right of appeal of Singaporeans like me who are suffering from financial distress and impecuniosity.

The legal right of all Singaporeans to appeal has been repeatedly endorsed by the Singapore Court of Appeal in several written judgments. For example, in Virtual Map (Singapore) Pte Ltd v Singapore Land Authority [2009] 2 SLR(R) 558 at paragraph [30], the Singapore Court of Appeal noted “the principle that there should be one tier of appeal as of right in civil actions in Singapore. Unsuccessful litigants in such cases should be entitled to appeal as of right to the Court of Appeal.” The Singapore Court of Appeal noted that there is “one tier of appeal as a matter of right” in its written judgment in IW v IX [2005] SGCA 48 at paragraph [22]. More recently, the Singapore Court of Appeal noted that “any judgment or order of the High Court is ordinarily appealable as of right” (Sinwa SS (HK) Co Ltd v Nordic International Ltd [2014] SGCA 63 at paragraph [32].

How do the statements quoted above square with my helplessness in attempting to gain access to the Court of Appeal?

Does my case make a mockery of the rule of law?

The right to appeal is an ancient legal right, which has been enshrined in the common law for centuries. As Lord Chief Justice Sir John Pratt said nearly three hundred years ago: “It is the glory and happiness of our excellent constitution, that to prevent any injustice no man is to be concluded by the first judgment; but that if he apprehends himself to be aggrieved, he has another Court to which he can resort for relief; for this purpose the law furnishes him with appeals…” (The King v The Chancellor, Masters and Scholars of the University of Cambridge (“Doctor Bentley’s Case”) (1723) 1 Str 557 at pages 564-565; 93 ER 698 at pages 702-703). English common law is part of Singapore law today, according to a Singapore statute called the “Application of English Law Act” which was enacted in Singapore in 1993, which says that “The common law of England … shall continue to be part of the law of Singapore.”

Therefore, the quotation from “Doctor Bentley’s Case,” which became part of the common law in England almost three hundred years ago, is still part of the common law in Singapore today. In “Doctor Bentley’s Case,” Cambridge University wrongfully deprived the plaintiff’s university degrees, much like NUS wrongfully denied me the award of my Master of Arts degree. In “Doctor Bentley’s Case,” the Court of King’s Bench ordered Cambridge University to restore Doctor Bentley’s degrees to him.

To anyone who says that I should ask the government to help me, let me remind you that I wrote to the Ministry of Education several times, starting from 2011, and most recently in 2017. The only result was that the Ministry of Education told me to go crawl back to NUS and beg NUS to let me have my degree. That was in 2011, after I enlisted the assistance of my Member of Parliament, who wrote to the Ministry of Education and asked the Ministry to launch a “formal inquiry” against NUS. The last time I wrote to the Ministry of Education was in 2017, and the only result was that the Ministry of Education repeatedly said that it was looking into my case and would get back to me, while refusing to provide any updates, and eventually the Ministry of Education ignored my requests for updates totally. It is now clear that the Ministry of Education lied to me in writing, since the Ministry obviously never had any intention of writing back to me, and the Ministry has not contacted me since 2017.

This is the same Ministry that promoted Lily Kong to the rank of President of Singapore Management University in January 2019, which was AFTER the High Court found that Lily Kong was guilty of wrongdoing, and AFTER Lily Kong lied in Court during trial (see paragraph [230] in Judgment for High Court Suit 667/2012, yet the High Court still allowed NUS to escape all liability for its wrongdoing.

So much for accountability from the Ministry of Education. So much for asking the government for help.

Why my case matters to every Singaporean

The right to appeal is an ancient legal right, which has been enshrined in the common law for centuries. As Lord Chief Justice Sir John Pratt said nearly three hundred years ago: “It is the glory and happiness of our excellent constitution, that to prevent any injustice no man is to be concluded by the first judgment; but that if he apprehends himself to be aggrieved, he has another Court to which he can resort for relief; for this purpose the law furnishes him with appeals…” (The King v The Chancellor, Masters and Scholars of the University of Cambridge (“Doctor Bentley’s Case”) (1723) 1 Str 557 at pages 564-565; 93 ER 698 at pages 702-703). English common law is part of Singapore law today, according to a Singapore statute called the “Application of English Law Act” which was enacted in Singapore in 1993, which says that “The common law of England … shall continue to be part of the law of Singapore.”

Therefore, the quotation from “Doctor Bentley’s Case,” which became part of the common law in England almost three hundred years ago, is still part of the common law in Singapore today. In “Doctor Bentley’s Case,” Cambridge University wrongfully deprived the plaintiff’s university degrees, much like NUS wrongfully denied me the award of my Master of Arts degree. In “Doctor Bentley’s Case,” the Court of King’s Bench ordered Cambridge University to restore Doctor Bentley’s degrees to him.

To anyone who says that I should ask the government to help me, let me remind you that I wrote to the Ministry of Education several times, starting from 2011, and most recently in 2017. The only result was that the Ministry of Education told me to go crawl back to NUS and beg NUS to let me have my degree. That was in 2011, after I enlisted the assistance of my Member of Parliament, who wrote to the Ministry of Education and asked the Ministry to launch a “formal inquiry” against NUS. The last time I wrote to the Ministry of Education was in 2017, and the only result was that the Ministry of Education repeatedly said that it was looking into my case and would get back to me, while refusing to provide any updates, and eventually the Ministry of Education ignored my requests for updates totally. It is now clear that the Ministry of Education lied to me in writing, since the Ministry obviously never had any intention of writing back to me, and the Ministry has not contacted me since 2017.

This is the same Ministry that promoted Lily Kong to the rank of President of Singapore Management University in January 2019, which was AFTER the High Court found that Lily Kong was guilty of wrongdoing, and AFTER Lily Kong lied in Court during trial (see paragraph [230] in Judgment for High Court Suit 667/2012, yet the High Court still allowed NUS to escape all liability for its wrongdoing.

So much for accountability from the Ministry of Education. So much for asking the government for help.

Why my case matters to every Singaporean

Every Singaporean should be frightened and outraged by my case, because, if a major public body like NUS can get away scot-free with blatant abuse of power, corruption, cover-up and retaliation against a whistle-blower, while spending at least $700,000 dollars (as NUS has claimed) fighting a legal battle against me in the High Court, then ANY public body in Singapore can get away with doing these things to ANY Singaporean (or, at least, to any ordinary Singaporean who is not a member of the privileged and entitled “elite” class).

My case shows that a public body in Singapore like NUS is “above the law” and can get away with abuse of power scot-free, with zero accountability and total impunity. My case will embolden other public bodies and elites to engage in abuse of power, cover-up and retaliation just like NUS did to me.

My case also shows that ordinary Singaporeans will find that their legal right to appeal to the Court of Appeal can be denied if they can't afford to pay $20,000 for “Security for Costs.”

My case also shows that, incredibly, the Court can even allow a wrongdoer (like NUS) to act as a “gatekeeper” who decides whether or not its victim will be allowed access to justice, and that wrongdoers can block appeals to the Court of Appeal.

My case also shows that Singaporeans who blow the whistle on blatant abuse of power by “elites” at NUS face the prospect of being bankrupted by NUS.

All of these facts make a mockery of the rule of law in Singapore.

Please see the video of the 17-minute speech about my case that I gave at Hong Lim Park, Singapore, on 16 March 2019.

For more information about my case, see the following articles:

Former NUS student who fought 12-year legal battle against University questions former Vice-Provost’s presence on the NUS Review Committee on Sexual Misconduct

Jeanne-Marie Ten: Appointment of former NUS Vice-Provost Lily Kong as President of SMU “is very wrong”

Jeanne-Marie Ten: Appointment of former NUS Vice-Provost Lily Kong as President of SMU “is very wrong”

Local Girl Claims she was Unfairly Expelled by NUS after Supervisor Stole her Thesis

“All I’m asking the court is to give me a sort of leave of absence…let me rest” – Jeanne-Marie Ten struggles with depression over case against NUS

Embattled MA Student Seeks Justice, Raises Funds Through Give Asia

“All I’m asking the court is to give me a sort of leave of absence…let me rest” – Jeanne-Marie Ten struggles with depression over case against NUS

Embattled MA Student Seeks Justice, Raises Funds Through Give Asia

Donation Details

It is an uphill battle but I shall continue in my struggle to get justice. If you wish to help me with my court filing fees, the two sets of "Security for Costs" and related legal expenses such as court transcripts, here are the donation details.

Paypal

tljvnus@gmail.com

It is an uphill battle but I shall continue in my struggle to get justice. If you wish to help me with my court filing fees, the two sets of "Security for Costs" and related legal expenses such as court transcripts, here are the donation details.

Paypal

tljvnus@gmail.com

PayLah!

93884036

Bank

POSB Everyday Savings Account 193-69702-0

Ten Leu Jiun Jeanne-Marie

DBS Bank Pte Ltd

12 Marina Boulevard,

DBS Asia Central,

Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3,

Singapore 018982

Singapore

Bank swift code:

DBSSSGSG

Branch code:

081

Thank you!

Bank

POSB Everyday Savings Account 193-69702-0

Ten Leu Jiun Jeanne-Marie

DBS Bank Pte Ltd

12 Marina Boulevard,

DBS Asia Central,

Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3,

Singapore 018982

Singapore

Bank swift code:

DBSSSGSG

Branch code:

081

Thank you!